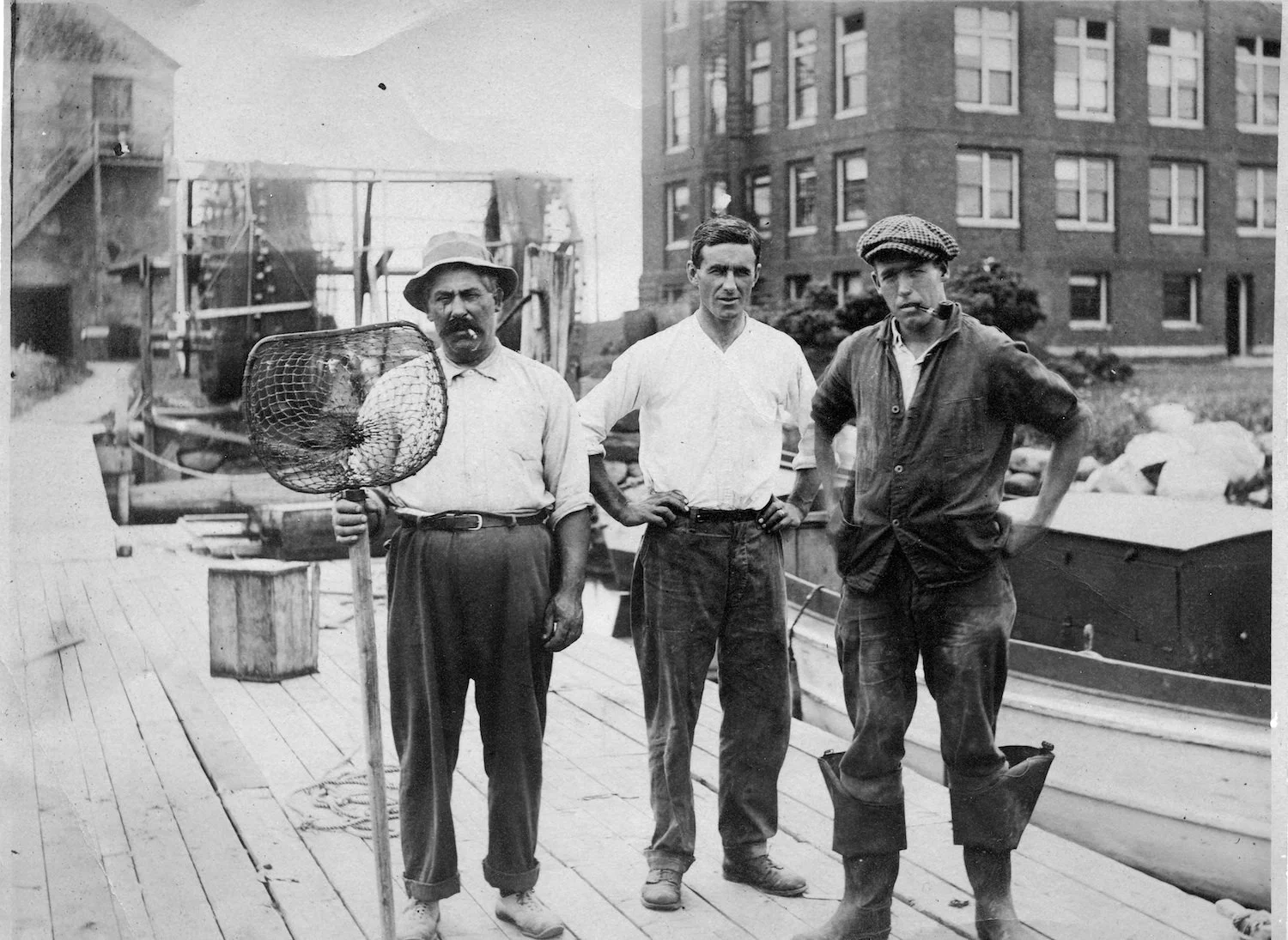

There was no doubt that Alegrnon Leathers was a character but so were several other members of the “Collecting Crew” of the supply department at the Marine Biological Laboratory before WWII. Take the long-bearded “Colonel”, for example, who liked to sit in the sun on the front lawn of the Crane building, picturesquely mending fishing nets. Or taciturn Sam Gray, one of the collectors who went out daily in boats to dredge or net starfish, sea urchins and other creatures from the sea bottom ofr dig them from the mid flats and beaches. His love was obscure marine worms. In fact even the logo of the supply department, the living-fossil horseshow crab, was a little offbeat.

Algy had two functions on the crew. First, he was the chief shipping clerk, spending much of his time packing specimens into jars or barrels of formalin to go to inland collebes and universities all ov er the country for their classes in zoology. Second, he was the one who injected starfish and dogfish with red, yellow and blue starch to delineate their vascular systems Algy also stood out because he was afflicted with a terrible stammer. He could converse with children who were watching him do his injections, or with friends, one at a time, but in a group or with strangers he was lost.

When I first knew him Algy lived in a 12x20, two story tarpapered house on the downhill end of a sloping lot next ot the house where I eventually came to live. In front of his house, at a higher level, was a cleared flat place with some masonry laid up around one corner. This, I was told, was the site of Algy’s future real house, the one he planned to build for the bride who was in prospect when he first came to the village in about 1910 as a Cornell graduate. Over the years he had been filling in and leveling the space by diverting and that washing down from the unpaved road above. But somehow the wedding never quite came off, and now, in his fifties, Algy lived alone in his tempo, perforce a semi-recluse because of his stammer. He did, however, sing in the Methodist choir, and he belonged to the volunteer fire department. Whenever “The Cow”, the village fire alarm, brayed in the night we would hear him roar off in his model A, successor to his T.

In the winter of 1943 Algy had a fatal heart attack and his heir, a n elderly minister, was happy to sell us the shack for our overflow population. Grandpa Specht gave it a transfusion of electricity from our house, and some bunk beds made it a usable dormitory while we dealt with Algy’s furnishings, an arresting mix of delixe and primitive. There was coppyer plumbing throughout. There were a new modern (1920s) bath tub and toilet at one end of the second-floor bedroom, a stainless steel hot water heater in the damp and dark cement-block basement and some finely crafted bookshelves and cabinetry in the living room upstairs. These items, along with the fiber-board of the inside walls of the shack, represented Algy’s using up of materials first assembled for the splendid house-to-be. Neither the hot water tank nore the tub had been connected.

The shelves beside the basement tool bench were loaded with dozens of White Owl cigar boxes. Some held neatly sorted nuts-and-bolts and some were full of cigar ashes. Severeal were crammed with defunct dollar watches in various stages of dissassembly and others had a mix of small brass valves, tubes and ambigiuous fittings. Outside the basement door were many wine jugs lying on a platform of ashes from the bucket-a-day coal stove in the living room.

Besides the parlor stove and bookshelves the living room had a sink and platform rocker. Since Algy took his meals in the Laboratory’s mess hall in the summer, and at a boarding house in the winter, there was no true kitchen. A coffee pot and frying pan suggested the limits of his cooking.

Algy’s tastes in reading were catholic, including as they did a variety of coffee-table types such as “History of the Civil War”, “Manners and Customs of Mankind”, and “Wonders of the World”, college textbooks, a complete set of international Cooresspondence school manuals, novels, speciality items such as “Fifteen Thousand Useful Phrases”, “Wise Cracks”, and “Sight Without Glasses”, and innumerable “how to” books of the sort advertised in the back of “Popular Mechanics”, Algy’s magazine of choice. The novels lincluded a few with titles suggesting naughty goings-on or torrid romance under exotic stars. Unfortunately these volumes could have provided little solace for a lonely man, being uniformly innocuous, at least in comparison with the ordinary fare of today.

Algy was certainly in self-improvement. He was also into recycling. Everyong knows that ashes have valuable plant nutrients - hence those boxes of cigar droppings preserved for a potential garden. And those dozens of verern shoes under the bed upstairs. Who knew when one would need a leather washer or hinge? As one packrat to another I understood Algy. You never know when something will turn out to be useful.

Though Algy lacked some amenities, we know he spent many a pleasant and settled Woods Hole evening, in his rocker in front of the cosy stove and kerosene lamp, engrossed in reasding, sipping wine and smoking his White Owls. The proof of his progress from ambition to comfrotable reality was the six inch mountain of cigar ashes that had built up on the floor to the right of the chair arm.